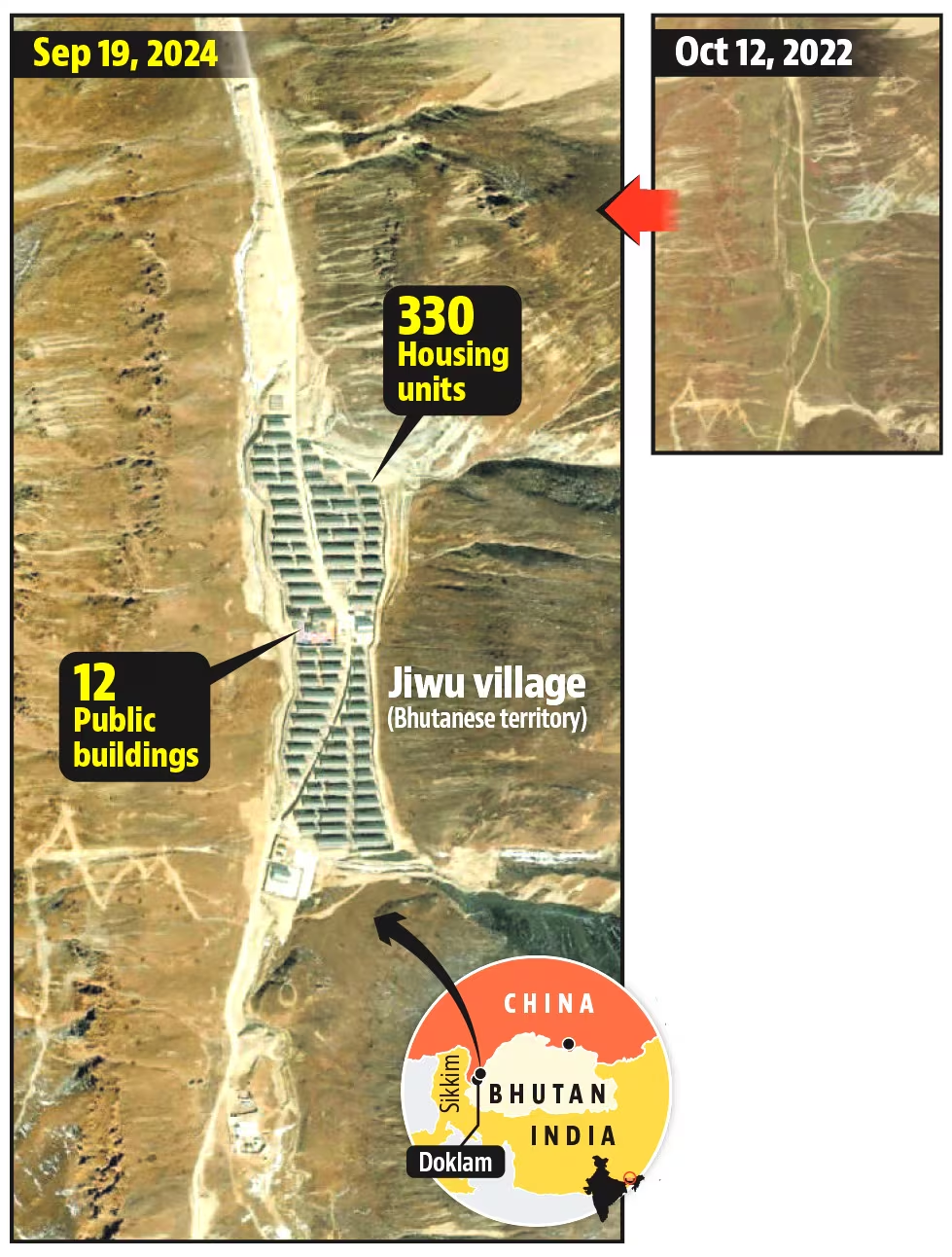

China has built at least 22 villages and settlements over the past eight years within territory that has traditionally been part of Bhutan, with eight villages coming up in areas in proximity to the strategic Doklam plateau since 2020, according to satellite imagery.

The eight villages in Bhutan’s western sector, close to Doklam, are all strategically located in a valley or a ridge overlooking a valley that China claims, and several are close to Chinese military outposts or bases. The largest of the 22 villages detected by observers and researchers – Jiwu, built on a traditional Bhutanese pastureland known as Tshethangkha – is also located in the western sector.

The location of these villages has alarmed China watchers in New Delhi, especially since the strengthening of the Chinese position in this strategic region could increase the vulnerability of the Siliguri Corridor, or the so-called “chicken’s neck”, a narrow stretch of land connecting India’s mainland to the northeastern states.

Doklam was the site of a 73-day standoff between Indian and Chinese troops in 2017, when New Delhi intervened to prevent the construction of a road and other facilities that would have given China access to the southern-most part of the plateau. Though front line forces of both sides pulled back from the region at the end of the standoff, satellite images from recent years have shown stepped-up Chinese construction activity around Doklam.

There was no response from India’s external affairs ministry for a request for comment on the development.

In recent years, Bhutanese authorities have denied the presence of Chinese settlements on Bhutan’s territory, and former prime minister Lotay Tshering created a flutter when he told a Belgian newspaper in 2023 that the Chinese facilities “are not in Bhutan”.

Bhutan did not respond to the queries on the matter.

Since 2016, when China first built a village in territory understood to be part of Bhutan, Chinese authorities have completed 22 villages and settlements consisting of an estimated 2,284 residential units and relocated almost 7,000 people to previously unpopulated areas of Bhutan, according to a recent report by Robert Barnett, research associate at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS).

China has annexed about 825 sq km “that was formerly within Bhutan”, constituting little more than 2% of the country’s territory, according to the report titled “Forceful Diplomacy: China’s cross-border villages in Bhutan”. China has also moved an unknown number of officials, construction workers, border police and military personnel into these villages. All the villages are also linked by roads to Chinese towns.

Seven settlements were built since early 2023, “signalling a marked increase in the speed and extent of construction in the annexed areas”, and three villages are set to be upgraded to towns, the report said.

Barnett wrote in the report that China’s objectives in Bhutan’s western sector “have been focused on acquiring and securing the Doklam plateau and adjoining areas”. The eight villages in the western sector form a 36km line running from north to south, with an average of 5.3km between each village. They were built in an area that, according to historians, was ceded to Bhutan by the then ruler of Tibet in 1913.

Ashok Kantha, who served as India’s envoy to Beijing during 2014-16 and is an honorary fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies, said China’s construction of villages within Bhutanese territory amounted to a violation of the agreement signed by the two countries in December 1998 on peace and tranquillity in border areas.

The China-Bhutan agreement states the two sides “agree to maintain peace and tranquillity in their border areas pending a final settlement of the boundary question, and to maintain status quo on the boundary as before March 1959”. It further states that both sides will “refrain from taking any unilateral action to change the status quo of the boundary”.

Kantha said these villages had been built in areas that were on Bhutan’s side of the traditional or customary boundary on Bhutanese maps. “In 2017, there was a pullback from the standoff point [at Doklam] but the Chinese kept entrenching their presence in different ways – villages, road construction and patrolling. They are essentially creating a fait accompli,” he said.

The villages, he said, are part of a pattern of China “changing facts on the ground incrementally and systematically”. This is similar to the pattern in the South China Sea, where China created artificial features and militarised them. “The Bhutanese are not in a position to challenge them because of the power asymmetry,” he said.

“This is all part of China’s characteristic of pursuing its claims while disregarding past commitments and the position of other countries, and getting away with it,” Kantha said. “For us, it matters because it is in a sensitive area close to the Siliguri Corridor.”

Barnett said the primary question for India in the context of these developments is the issue of Doklam. “But Bhutan, which is treaty-bound to respect India’s security interests, has said the Doklam issue will be decided on a trilateral basis, not by Bhutan. So, it seems very unlikely that any decision on Doklam would be made without India’s involvement,” he said.

“In the long term, the larger issue is whether China’s use of extreme pressure – or more precisely, force – will succeed in pushing Bhutan away from India’s sphere of influence and into that of Beijing. It now seems Bhutan has already had to give up significant territory to China, and that India was unable to help prevent that,” Barnett said.

“In the near future, it seems inevitable that Bhutan will have to allow China to open an embassy in Thimphu, leading to increased trade with China. So overall this issue between Chinese and Indian influence in Bhutan is going to be decided by which side can win over the Bhutanese people, and which can bring them real benefit,” he said.

Over the past four years, relations between India and China dipped to their lowest point since the 1962 border war because of a military standoff in Ladakh sector of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) that began in April-May 2020. On October 21, the two sides reached an understanding that paved the way for disengagement of frontline forces at Demchok and Depsang, the two remaining “friction points” on the LAC. Two days later, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping met on the margins of a Brics Summit in Russia and agreed to revive several mechanisms to address the border dispute and normalise bilateral relations.