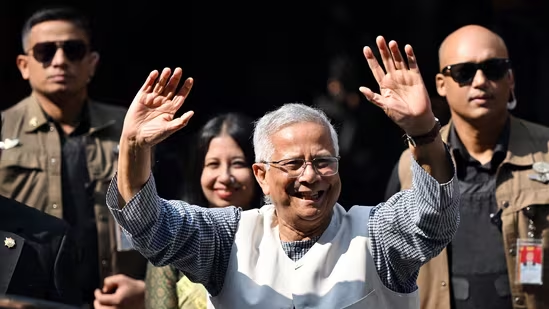

Brought to the forefront as the face of the appeal for peace in 2024 amid the violent student uprising, Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus, the chief adviser of the interim government, is one of the most important figures of the Bangladesh elections 2025, the first general polls since the ouster of former prime minister Sheikh Hasina.

Bangladesh, over a year after the student uprising brought Sheikh Hasina to India in exile and Yunus to Dhaka to head the government on an interim basis, stands at a historic crossroads.

Yunus has consistently emphasised that his role is to oversee a smooth transition to an elected government, not to remain a political figure beyond the polls. He has publicly stated he has “no desire to be part of the next elected government” and that neither he nor his advisers intend to retain power after the vote. What lies ahead for Yunus?

A caretaker, not a political contender

The stance of not remaining a political figure beyond the election positions Yunus as a neutral steward of the electoral process, reinforcing his global reputation as a civil society leader rather than a partisan politician. His focus, therefore, lies on credible elections rather than political ambition.

Muhammad Yunus was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 along with Grameen Bank for their work to “create economic and social development from below”. Grameen Bank’s objective since its establishment in 1983 has been to grant poor people small loans on easy terms, so-called microcredit, and Yunus was the bank’s founder.

Following studies in Bangladesh and the United States, Yunus was appointed professor of economics at the University of Chittagong in 1972. When Bangladesh reeled under a famine in 1974, Yunus, in a bid to do something more for the poor beyond simply teaching, decided to give long-term loans to people who wanted to start their own small enterprises. This initiative was extended on a larger scale through Grameen Bank, according to nobelprize.org.

For Yunus, poverty means being deprived of all human value. He regards microcredit both as a human right and as an effective means of emerging from poverty: “Lend the poor money in amounts which suit them, teach them a few basic financial principles, and they generally manage on their own,” Yunus claims.

Managing an unprecedented political landscape

The Awami League (AL) – once the country’s dominant political force led by Sheikh Hasina – is barred from contesting, with Hasina in exile and facing multiple convictions. Hasina was awarded death penalty in November last year by the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) to Sheikh Hasina, 78, for ordering the use of lethal force while cracking down on the protests in August 2024, during which she fled to India. The ICT awarded a separate sentence of imprisonment until death to Hasina for being complicit in crimes against civilians by law enforcement and armed cadres of her Awami League party.

The relations between India and Bangladesh came under strain after the interim government headed by Muhammad Yunus came to power following the collapse of the Hasina government.

Traditional support bases are fractured: many loyalist voters are disengaged or considering abstention, while other parties like the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jamaat-e-Islami have emerged as key rivals.

Rising communal tensions and violence, particularly against minority groups, have drawn both domestic criticism and international concern, complicating the interim government’s credibility. Communal tensions have escalated in the country, especially after the killing of prominent student leader Sharif Osman Hadi of Inqilab Moncho in December last year.

This volatile backdrop necessitates a nonpartisan Yunus to manage security, fairness, and public trust in a highly polarised environment.

Yunus, who returned from exile in August 2024 at the behest of protesters to lead the caretaker government as “chief adviser”, will step down after the polls.

Yunus said he inherited a “completely broken” political system, and championed a reform charter he argues is vital to prevent a return to authoritarian rule, with a referendum on the changes to be held on the same day as polling.

“If you cast the ‘yes’ vote, the door to building the new Bangladesh will open,” Yunus said on January 19, in a broadcast to the nation urging support for the referendum, according to AFP news agency.

Criticism and high stakes

Yunus, in October 2025, said he will supervise administrative reshuffles to ensure local officials can maintain peace and order during polling.

He urged full security at polling stations, including enhanced police measures, to counter election-period violence and disruptions.

Yunus has warned of “internal and external attempts” to thwart the polls, reflecting concerns over propaganda and interference.

“If you cast the ‘yes’ vote, the door to building the new Bangladesh will open,” AFP news agency quoted Yunus as saying on January 19 in a broadcast to the nation urging support for the referendum.

He also warned he was “concerned about the impact” a surge of disinformation could have.

“They have flooded social media with fake news, rumours and speculation,” Yunus said, blaming both “foreign media and local sources”.

While these moves highlight Yunus’s balancing act – delivering a credible democratic process while contending with a fragmented political order and social unrest – not everyone accepts his roadmap without reservation.

Political parties have accused him of confusing or “misleading” remarks on election timelines. The Bangladesh Awami League of Sheikh Hasina outright rejected the election schedule announced by the country’s interim government’s Election Commission for the February 12, 2026, terming the move by the EC as “illegal” and accusing the Yunus-led government of being a “killer-fascist” clique that cannot ensure a free and fair vote.

In a strongly worded statement issued on Thursday, the Awami League had said after the announcement of the poll date in December last year that it has “closely reviewed the election schedule announced by the illegal, occupying, killer-fascist Yunus clique’s illegal Election Commission” and declared that the current administration cannot ensure transparency, neutrality, or reflection of the people’s will.

“The Bangladesh Awami League has closely reviewed the election schedule announced by the illegal, occupying, killer-fascist Yunus clique’s illegal Election Commission. It is now clear that the current occupying authority is entirely biased and that under their control, it is impossible to ensure a fair and normal environment where transparency, neutrality, and the people’s will can be reflected. Elections are the measure of public popularity. The Awami League is an election-oriented party. The Awami League has the strength, courage, and capacity to stand before the people,” Hasina’s party had said.

Rising violent incidents linked to political rivalry have heightened fears that the country could regress into instability. In her first public address from India, Hasina had accused the Yunus government of sending democracy “in exile” and allowing human rights violation, violence against minorities as well as sexual assault against women.

“Human rights have been trampled into the dust. Freedom of the press has been extinguished. Violence, torture, and sexual assault against women and girls remain unchecked,” she had said. “Religious minorities face continuous persecution. Law and order have collapsed.”

Yunus’s credibility – and the election’s legitimacy – will depend largely on his ability to moderate these tensions and ensure broad participation.

Whether Yunus is remembered as a stabilising force or a caretaker caught in systemic dysfunction will emerge only with time. His leadership is not just about administering an election: it’s about setting the tone for Bangladesh’s post-Hasina political architecture.

Bangladesh’s leading prime ministerial contender is Tarique Rahman, 60, who heads the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). He returned home in December after nearly two decades in exile in London following a youth-led uprising that toppled long-time leader Sheikh Hasina, a bitter rival of his mother, the country’s first woman prime minister Khaleda Zia.

Zia died on December 30 last year aged 80.

The BNP’s main rival in the February 12 election is the Islamist group Jamaat-e-Islami, once banned but now resurgent.